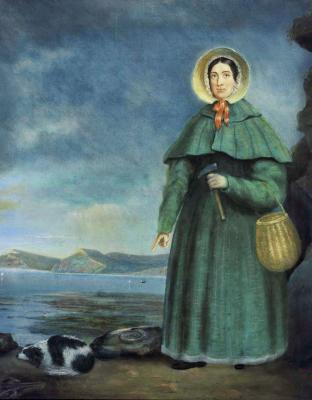

Despite humble beginnings as the daughter of a poor cabinet maker, Mary Anning was one of the greatest fossil hunters of all time. Taken together, her finds provide key evidence for extinction, which represented a significant departure from the traditional Biblical theories of creation.

Mary Anning was born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, where a geological formation called the 'Blue Lias', composed of alternating layers of limestone and shale laid down as sediment on a shallow seabed about two hundred million years ago, is one of the richest fossil-hunting grounds in Britain.

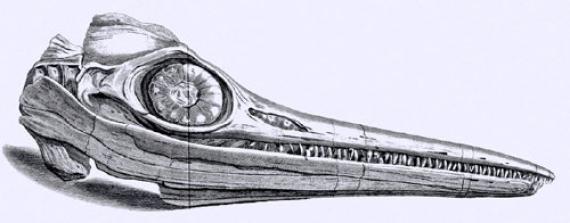

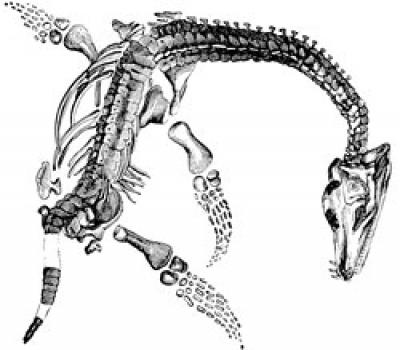

Anning was one of ten children of whom only two survived. She was introduced to fossil hunting by her father. Like many others in Lyme Regis he supplemented his income selling fossils ('curios') to tourists. After her father died of consumption, Mary quickly assumed a leading role in the family's fossil-hunting business. Aged just eleven, she generated considerable interest when she dug up an icthyosuar skull and skeleton and sold it to local lord of the manor, Henry Hoste, who in turn sold it to William Bullock for his Museum of Natural Curiosities in London, where it was displayed as a 'fish-lizard'. More big finds were to follow. In 1823, Anning found the first complete skeleton of the long-necked Plesiosaurus (sea dragon), and in 1828 she found the first British example of a Pterodactylus, displayed in the British Museum as a 'flying dragon'.

Mary Anning risked her life to collect the fossils from underneath dangerously unstable cliffs, narrowly escaping death in a landslide in 1833 that buried her dog alive. By 1826 she had made enough money from fossil hunting to open a glass-fronted shop in Lyme Regis. Geologists and fossil collectors from all over Europe visited the shop, attracted by Anning's formidable reputation as well as her wit, intelligence and expertise. Despite a lack of formal education, Anning schooled herself thoroughly in geology and anatomy, although she was denied proper access to the British scientific community because of her gender and social class. (Women were not permitted to join the Geological Society until the twentieth century). Many of her finds were described by other scientists in articles that made no reference to her, causing her to complain that 'The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.'

Mary Anning did have supporters, however. After she lost all her savings in a bad investment, her friend, William Buckland, persuaded the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the British government to give her an annuity of around twenty five pounds a year, and when Anning was diagnosed with breast cancer, the Geological Society clubbed together to raise money to help with her expenses.

Anning died in 1847, aged forty seven. Her reputation has continued to grow since her death. Mary Anning is referenced in several historical novels, including 'The French Lieutenant's Woman' and 'Remarkable Creatures' by Tracy Chevalier, in which the main characters are Mary Anning and her friend. Elizabeth Philpot. In 2010 the Royal Society included Mary Anning in its list of the ten British women who have most influenced the history of science.

- History